You may think you’re just playing games to keep your brain active, but you’re really helping researchers understand how lifestyle and aging affect cognitive performance.

In this vast digital world, many of the details of our public and private lives are automatically captured by websites, online programs and smartphone apps.

By default, photos taken with your iPhone are tagged with your location, information about your phone and sometimes even your personal data. Facebook and Google are also notorious for using your information to serve up an endless stream of relevant (albeit creepy) advertisements that seem to know what you want to buy before you do.

In fact, every time we log into our favorite social networking sites or download apps onto our smartphone, we tacitly allow third-party businesses to capture, catalogue and use our personal data.

The digital breadcrumbs that we leave behind wherever we go online are readily snatched up by these businesses in hopes of turning our fondness for cats and our preference for indie music from the 80s into a quick sale.

Even the U.S. government has jumped into the fray, gathering armloads of phone records and emails of Americans and non-Americans alike, hoping to find the proverbial terrorist in a haystack.

As disconcerting as it is to have our digital selves unwittingly exposed to the world (or more likely, to covert agencies and equally shady marketers), the information that is collected about the way we use the Internet and smartphone apps can be applied to more beneficial purposes.

Traditional Cognitive Function Research Involves Much Legwork

One such use of our electronic personal data is health research, especially that dealing with brain performance. These types of cognitive studies involve looking at the factors that affect the functioning of our brain, such as diet, lifestyle and aging.

One such use of our electronic personal data is health research, especially that dealing with brain performance. These types of cognitive studies involve looking at the factors that affect the functioning of our brain, such as diet, lifestyle and aging.

Traditionally, researchers have studied cognitive performance by recruiting real-life people and using a variety of tests to examine mental abilities like working memory, verbal fluency and basic arithmetic skills. The specific tests used depend upon the questions being asked by the researchers.

As with most research that requires interacting one-on-one with people, these kinds of studies can be very time intensive. Volunteers need to be identified, recruited, tested one or several times, and paid (yes, people in research studies often receive compensation for their efforts).

As a result, cognitive research has been restricted in scope due to a lack of time, as well as a lack of funding. To answer a specific question, researchers may need thousands of participants. Many times, though, they only have enough funding for 100 people.

These types of studies also tend to recruit volunteers who are not representative of the larger population, often including mainly undergraduate students who are readily available at every college and eager for a few extra bucks.

All of this limits the types of questions that can be answered, leaving cognitive function researchers to make do with what little they have.

Internet Has Changed the Collection of Personal Information

With the growth of the Internet, this has all changed. Each time you log onto your favorite social networking site or use a web-based program or app, information about you—your location, your likes and dislikes, your habits, your health—flows into a large pool along with information on countless other people.

With the growth of the Internet, this has all changed. Each time you log onto your favorite social networking site or use a web-based program or app, information about you—your location, your likes and dislikes, your habits, your health—flows into a large pool along with information on countless other people.

In reality, there are many such pools, each one tended by a specific business (or other entity). As the pools grow in number and size, the possible uses of the data increases exponentially. While this information should open up a whole new world of research, it is difficult to make sense out of what is essentially an ocean of data on millions of individuals.

Duke University researchers have recently attempted to use this type of crowdsourcing—leveraging the collective wisdom of the masses—to answer questions about how the brain functions and what affects our mental abilities.

In a study published in the journal Frontiers of Human Neuroscience, the researchers outlined two possible uses of information collected by Lumosity, a web-based brain training platform.

Lumosity was not originally designed as a research tool. Instead, its main goal is to help users improve their mental abilities through a series of cognitive training exercises and tests. Along the way, though, Lumosity has begun collecting other information about users, including their health, lifestyle and real-world mental activities.

This has led to the creation of the vast Lumosity pool of information about brain function, one that includes over 600 million tasks performed by over 35 million people in 231 countries.

Brain Function Studies Tap Into Personal Electronic Information

By tapping into this resource, researchers were able to answer questions about how lifestyle choices—namely sleep and alcohol—affect brain function, and how mental abilities change with age.

By tapping into this resource, researchers were able to answer questions about how lifestyle choices—namely sleep and alcohol—affect brain function, and how mental abilities change with age.

These questions, of course, are nothing new. Many researchers have tackled them before, using the proven method of recruiting people and talking to them face-to-face (consider it the analog method, compared to Lumosity’s digital upgrade).

What the Duke researchers found tracked pretty closely with previous research (such as the large Whitehall II study in the UK). Here’s a quick overview of their results:

- Cognitive performance was greatest for people who slept 7 hours a night, dropping off for more or less sleep.

- Moderate drinkers of alcohol (1 to 2 drinks per day) did better on certain mental function tests than heavier drinkers and abstainers.

- Mental abilities decreased with age, but declined faster for fluid intelligence tests (things like working memory).

As impressive as this sounds—you can just jack into the net and find out how many points you’ll lose by drinking the night before your physics exam—much work remains to be done.

Limits of Crowdsourcing Brain Function Research

The size of Lumosity’s data pool is impressive, but it is far from a pristine body of water. For example, people who sign up to use their web-based brain training actually opt into the system. As with studies based solely on the performance of undergraduate students, it’s difficult to say that the results apply to everyone (what about people of lower incomes? or technophobes?).

The size of Lumosity’s data pool is impressive, but it is far from a pristine body of water. For example, people who sign up to use their web-based brain training actually opt into the system. As with studies based solely on the performance of undergraduate students, it’s difficult to say that the results apply to everyone (what about people of lower incomes? or technophobes?).

There’s also the question of whether the answers that people give about their lifestyle habits are correct (are they underestimating their drinking habits? do they sleep 7 hours a night, but wake up several times throughout?).

Even more worrisome is that people using the system take Lumosity’s mental tests under different conditions. In most research, the testing environment is carefully controlled in order to eliminate (or minimize) the effect of things like lighting on the results. With Lumosity data, those types of conditions are all over the map, leaving us to wonder whether decreased mental performance is due to overdrinking and not because someone took the brain tests at a bar.

The researchers admit that more work needs to be done to bring clarity to this murky ocean of data. In order to determine how sound the data is, they will need to undertake more controlled studies (similar to what has been done up-to-date with other cognitive function research).

Still, as with many crowdsourcing endeavors, having extremely large collections of people (or information) can sometimes smooth out the roughness of the data and give you a pretty accurate “best guess.”

In spite of its shortcomings, the Lumosity study provides a glimpse into the future of research. There could come a day when your iPhone can tell you that you should wait to take a picture of your girlfriend, because 90 percent of men who’ve had a drink before snapping a photo of their significant other break up with her within 3 months.

If that isn’t a more noble use of personal data, then I don’t know what is.

__________

References:

Sternberg, D., Ballard, K., Hardy, J., Katz, B., Doraiswamy, P., & Scanlon, M. (2013). The largest human cognitive performance dataset reveals insights into the effects of lifestyle factors and aging Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7 DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00292

Photos:

High-density EEG, PicasaWeb by Steven Laureys

I am drinking with my mind, Flickr by anfearglas

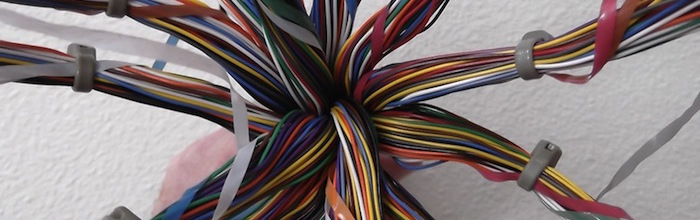

Telephone cable resembling brain neurons, Flickr by brewbooks

Telephone switchboard, Flickr by ABC Archives

Large crowd in Paris, Flickr by James Cridland